8. Secrecy and democracy

“MPs who

campaigned for Leave in order to ‘take back control’ should wake up: it’s not parliament which now has

control, it’s the the prime minister.”

Caroline Lucas MP, former leader of the

Green Party101101

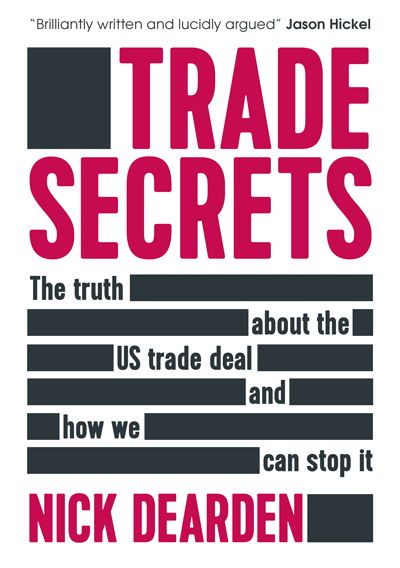

On 19 November 2019, Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn went head- to‑head with Conservative leader Boris Johnson on national television. With under a month to go until the general election, it was a critical debate. And Corbyn had brought a prop with him – a pile of papers which had been almost entirely blacked out.

These were the redacted details of the trade talks the British government had been conducting with the US administration, as provided by the Department for International Trade. And the fact that virtually the only thing still visible on these papers were the page numbers made one thing very clear – as far as the British government was concerned trade negotiations should take place in secret, with no meaningful role for the public or our elected representatives.

The papers that Corbyn held up had been released to Global Justice Now some months earlier. We had asked the government to disclose basic information about the trade talks: where and when they’d taken place, the agenda, details of those present and notes of the meetings. Initially we’d received nothing back, on the grounds that all such information was too sensitive for the public to view. But on appeal, we’d received a substantial amount of papers. The only problem is that we couldn’t read any of them because they had been censored.

In the event, the full papers were leaked on website Reddit and came to our attention a few days later. The leaks proved extremely helpful in writing this book and allowing us to see exactly what is ‘on the table’ in these talks. But the problem of our desperately archaic and opaque political system has not gone away. The fact remains that the deal described in these pages will be negotiated with virtually no transparency to either the public or parliament.

MPs cannot properly scrutinise the negotiations, they can’t approve or reject the government’s negotiating objectives and they can’t stop a trade deal passing into effect, however much they may dislike it. Trade deals are negotiated without the normal democratic checks and balances. And, given how these deals touch upon so many areas of our lives, this is an unacceptable democratic deficit.

Democratic deficit

Britain’s system for negotiating trade deals has changed little since the 1920s. International agreements were then seen as the business of the executive rather than parliament, and were negotiated under royal prerogative, largely bypassing parliament. As trade deals at that time were more limited affairs, concerned mostly with the mutual reduction of tariffs, perhaps there was some justification for this system. But as times – and trade deals – change, the British system stayed the same.

While Britain was a member of the European Union, trade matters were mostly dealt with in Brussels, with the elected MEPs gradually gaining significant powers over the negotiations. These powers were greatly enhanced during the TTIP negotiations, as the European Commision saw the damage that secrecy was having on public trust and began to fear that the whole deal could be derailed, as indeed it eventually was. Scrutiny powers were improved and today negotiating a trade deal in the EU entails a fairly extensive process including member state governments setting negotiating objectives, the Commission keeping parliament fully informed and taking its views into account, MEPs having the right to see all negotiating documents, an open and formal dialogue with civil society organisations, and, vitally important,

parliament getting a meaningful vote at the end. Indeed, for some trade agreements, all recognised parliaments in the EU, including some regional assemblies, must ratify the deal too. Many still think this is insufficient. In 2015, the EU Ombudsman Emily O’Reilly said: “Citizens are increasingly aware that TTIP will produce rules that impact on them in a manner analogous to how legislation impacts them… citizens expect and demand the right to know and to participate when it comes to TTIP… The impact [of transparency] is deemed to be overwhelmingly positive, ranging from enhanced legitimacy, heightened trust, an educated debate, and a better agreement in substance.”

In the US, Congress is also guaranteed a meaningful vote on trade agreements and, unless it signs away its authority, it even has the right to amend trade deals. Public consultation is mandatory, with specific guidelines for how to carry it out including a very large citizen advisory panel with access to confidential information.

Sadly, the British government has failed to transfer the powers of democratic oversight developed within the EU to the British parliament. British MPs do not have a right to vote or debate the government’s negotiating objectives, they don’t have a right to see the negotiating papers or to effectively scrutinise the government, and they are not guaranteed a debate or a vote once the trade bill is complete. Even if they are lucky enough to be granted a vote, they cannot stop the trade deal for more than a month, and – in any case – by this time it would already have been implemented.

The fight for trade democracy

Some MPs have put up a heroic fight to secure greater powers over trade deals, but to date their work has been rejected by the government. Five parliamentary committees have criticised the trade process and called for change, with one calling current procedures “anachronistic and inadequate”.102102

In the previous parliament, MPs from Labour, the Scottish National Party, Liberal Democrats, Plaid Cymru and the Green Party all sought to use the Trade Bill going through parliament to introduce a modern democratic framework for doing trade deals. In the House of Commons, amendments to the Trade Bill tabled by MPs like Caroline Lucas were defeated by the government’s majority. Then in the Lords, an amendment was successfully passed which would have given parliament proper power to scrutinise and, if necessary, stop trade deals – at which point the government shelved the whole bill to prevent the amendment becoming law. After the 2019 election the government brought in a new Trade Bill, without any of the new parliamentary powers.

A coalition of businesses, campaigners, trade unions and consumer groups have called for a model which would make trade negotiations transparent and democratic.103103 It includes:

- A debate and vote on the government’s negotiating objectives at the start of the process.

- Transparency throughout the negotiations so MPs can hold the government to account.

- A final debate and a meaningful vote on the final deal.

It is also important, given that trade deals can interfere with the power of devolved administrations, to give those administrations a role in overseeing trade negotiations. Again, the government has promised these governments little more than a regular chat.

Without these changes, trade deals will remain secret from the public, and will allow the British government startling powers to erode our standards and protections, our public services and our ability to control big business, with virtually no checks or balances.

What the trade papers say

When it comes to democratic accountability, we know the government’s position, because it has been set out formally. The more information that comes to light, the clearer it is that, in the words of a former trade official, Britain is “at the far end of the secrecy” spectrum.104104 We have also learned that the government has gone beyond even its usual opaque standards by signing a letter with the US promising to keep negotiating papers secret for as long as five years after a deal has been signed.105105 And we have discovered that the government is having trade talks with other governments that are so secret, we’re not even allowed to know who they are talking to.106106

Even the government’s apparent attempts at accountability have been shambolic and inadequate. Its consultation on the US trade deal sounds like a positive step, and it attracted nearly 160,000 responses, proving public interest in trade deals.107107 But sadly it gave no indication of what the UK’s objectives would be, or a meaningful assessment of the impact of a deal. It amounted to little more than asking people what they thought of the broad idea of trade with the US. Neither do ministers have to pay any attention to what the public thinks. Boris Johnson’s manifesto pledge that a trade deal would not affect food standards already seem to have been shelved, leading to a further erosion of trust in the government’s promises about this deal.108108

When it comes down to it, Britain will be conducting trade negotiations with countries that have far more transparent processes than we do. In the case of the US, congressional representatives will hold more power than our MPs over the terms of any deal. And if a trade deal with the EU takes place, it will surely be a supreme irony that our parliament, in a quest to ‘take back control’, will actually find it has less power over that deal than the European parliament we just left, and very likely less power than German MPs, Danish MPs, or even deputies in Belgium’s regional assembly.

References

-

‘Democracy dies in darkness. Today I’m fighting to preserve it as Boris Johnson turns off the lights’, Caroline Lucas, Independent, 8 Jan 2020

-

‘Constitution Committee recommends amendments to Trade Bill’, Lords Select Committee, parliament.uk, 15 Oct 2018

-

A Trade Model That Works For Everyone, Trade Justice Movement, 28 Jun 2018

-

‘UK government admits that secret trade talks are underway’, Global Justice Now, 14 Feb 2020

-

‘UK Accused Of Caving To US Demands For Trade Talks Secrecy’, Huffington Post, 7 May 2020

-

See note 104

-

‘Summaries of consultations on future FTAs published’, Department for International Trade, gov.uk, 18 Jul 2019

-

‘Boris Johnson facing backlash after scrapping pledge to keep chlorinated chicken out of British supermarkets’, Independent, 4 Jun 2020